How “The Hamptons” started as a quiet destination for American Art

As we gear up for summer Out East (and an exciting exhibition update), we take a look back at the history of artists on the East End.

Co-written by our very own Kristin Collins

Before it became a real estate headline or shorthand for summer status, East Hampton was quiet. The land was cheap, the skies were wide, and the air had that kind of peacefulness you surely didn’t get in the city. It wasn’t glamorous, it was unpolished and overgrown, full of old barns and weathered shingles that leaned into the wind.

In the 1940s, life here moved at its own pace. Fishermen hauled in their nets at dawn. Locals crabbed barefoot in the creeks. The city felt far away, and for the artists who came, that was the point.

There was something about this place, a pull that drew them out of Manhattan and into a slower rhythm of solitude. The beauty helped too. Away from the salons and studios, they found space to think, to make, to live.

Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner

For Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner, East Hampton (specifically The Springs) was the backdrop to their life as a pair, and where Pollock developed a style that changed American Art.

They met in the East Village, both artists. Krasner was sharp, serious, and already established. Pollock was volatile and unknown. She introduced him to Peggy Guggenheim (learn more about her from our previous post), who would become his patron, and later offered them a loan (a mere $2,000) to buy a small farmhouse in The Springs. They left the city in 1945, hoping the life outside the city might steady him.

Their life there was simple. She painted upstairs in the bedroom. He painted in the barn working barefoot, cigarette in hand, listening to jazz.

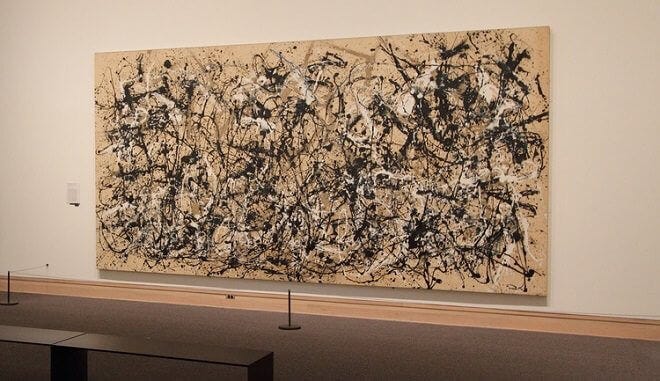

In that barn, Pollock began to unlearn everything he’d been taught. He gave up the easel, unrolled the canvas on the floor, and let the paint fall. The technique was primal, closer to cave painting than traditional fine art, but he brought it into the modern era. This was where his signature style was born. The drip technique took shape on those wide wooden planks, marking a shift that would help define American Abstract Expressionism.

By the early 1950s, Pollock had begun drinking again, and the distance between him and Krasner grew. In the summer of 1956, he crashed his convertible just a few miles from their home, with his 26-year-old mistress and her friend in the car. He was 44.

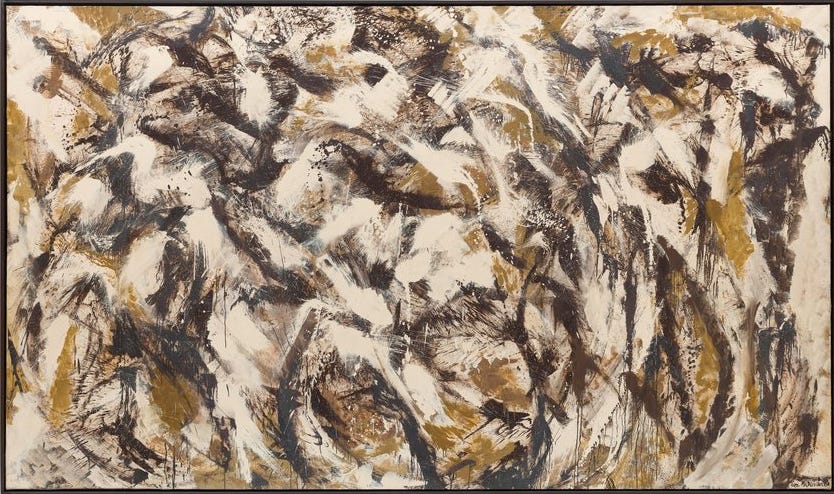

Krasner was known to pick up her paintbrush just two weeks after the funeral, even in the thick of her grief. She moved her studio into the barn where he had once painted, the wooden floors still marked with drips of dried paint. One of her most celebrated works, Polar Stampede, was created during this time.

Krasner had always been an artist in her own right, long before she was tied to Pollock. She studied under Hans Hofmann, one of the most respected teachers of modern art, and was often one of the only women in the room. She worked alongside artists like Louise Nevelson and Robert Motherwell, and spent her life pushing to be seen not as someone’s wife, but as an artist on her own terms.

When asked why she never had children with Pollock, she answered plainly: “I married him to be an artist, not a mother.”

Still, the story rarely centered around her. And it’s hard not to look at the numbers. In 2015, Pollock’s Number 17A sold for $200 million. As of 2019, Krasner’s highest-selling work at auction reached $11 million.

It was Krasner who introduced Pollock to Guggenheim. Krasner who found the house in East Hampton. And after it all, she was the one who made sure the legacy lasted. She established the Pollock-Krasner Foundation and helped turn their home and studio into a place people can still visit today, with the historic paint-splattered floorboards left exactly as they were.

We’re considering a group visit with our community this summer. Drop a comment if you’re in! Pollock-Krasner House Info

Where to See Jackson Pollock’s Work in NYC

Museum of Modern Art (MoMA)

MoMA holds several of Pollock’s major works, including the iconic One: Number 31, 1950, a cornerstone of Abstract Expressionism.The Metropolitan Museum of Art (The Met)

The Met features key pieces from his career, such as Autumn Rhythm (Number 30) (1950)

Where to See Lee Krasner’s Work in NYC

Museum of Modern Art (MoMA)

MoMA holds one of Krasner’s significant works, Untitled (1949)

The Whitney

Visit “The Seasons” on the 7th floor on permanent display

Willem and Elaine de Kooning

Willem and Elaine de Kooning first came to East Hampton in 1948 as weekend guests of Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner. The four were part of the same art world. If you read The Art of Rivalry with us in our book club, you’ll remember the dynamic between de Kooning and Pollock, a mutual respect, some competition, and a lot of pressure to define what modern American painting would become.

More than a decade after their visit , Willem and Elaine bought a home of their own in The Springs, not far from the Pollock-Krasner house.

"I wanted to get in touch with nature. Not painting scenes from nature, but to get a feeling of that light that was very appealing to me, [in East Hampton] particularly...It would be very hard for me now to paint any other place but here."

—Willem de Kooning

Willem designed the house himself, starting with the art studio. It was a thoughtful, functional space, built entirely around how he liked to work. A butterfly ceiling supported by steel trusses, a 40-foot skylight, and a glass wall that brought in the northern light he loved. Not much like Pollock’s barn.

Still, de Kooning gave credit where it was due. “Pollock broke the ice,” he famously said, acknowledging that it was Pollock who opened the door to a new era in American painting.

His own work offered another definition of Abstract Expressionism within the chapters of the American art movement He became known for combining abstract forms with recognizable figures, especially women. His paintings were large, physical, and full of movement, and unlike some of his peers, he never fully left representation behind.

The Hamptons reminded Willem of his childhood in Holland, and once the studio was complete, he stayed for the rest of his life. Today, it’s been transformed into a creative retreat, filled with light and still a space for making.

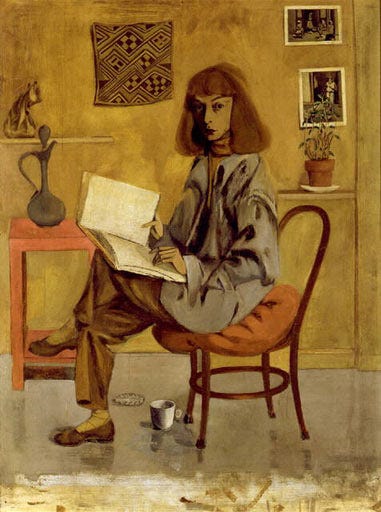

Elaine de Kooning was a painter and writer who was also, independently deeply involved in the art scene of the time. She painted expressive portraits, most famously of JFK, and wrote sharp, thoughtful essays about art for large publications. She was a respected voice in the Abstract Expressionist circle and helped shape how the movement was talked about and understood.

Where to see Willem de Kooning’s work in New York City:

MoMA holds a number of his major pieces, including the iconic Woman I (1950 52).

The Met features earlier works like Attic (1949) and Black Untitled (1948).

Gagosian in Chelsea is currently showing Willem de Kooning: Endless Painting, an exhibition spanning works from 1944 to 1986, including two sculptures—Clamdigger (1972) and Standing Figure (1969–84). Til June 15th. Learn more here.

Where to see Elaine de Kooning’s work in New York City:

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

de Kooning's Self-Portrait (1946), an oil and charcoal on canvas.

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

Her dynamic painting Juarez (1958) is part of the Guggenheim's collection.

Peter Beard

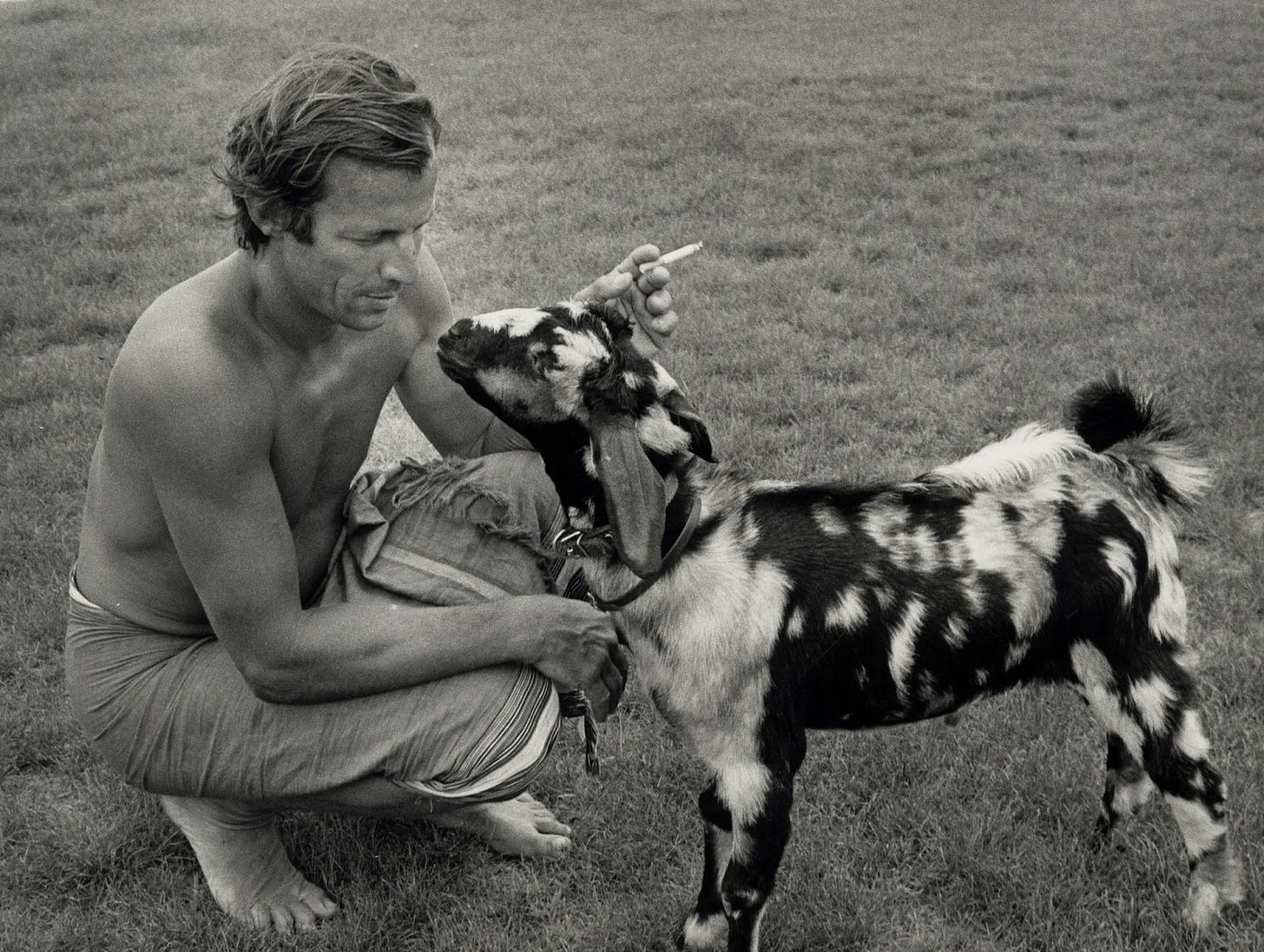

Peter Beard lived on the cliffs at the far edge of Montauk, in a house filled with journals, bones, and photographs. But he was rarely in one place for long. He split his life between Montauk and Kenya. His infamous journals, collaged with photos, feathers, leaves, ink, and even his own blood, became his signature. They documented wildlife, tribal life, and his own personal mythology with a raw, unfiltered beauty. He was a photographer, but also a kind of visual storyteller, somewhere between anthropologist, archivist, and provocateur.

He was known as much for his work as for the way he lived. Beard partied with Andy Warhol (who called him a “modern Tarzan”), was close with Mick Jagger and Jackie Onassis, and married supermodel Cheryl Tiegs. He was charming, unfiltered, a little (very) reckless, and full of contradictions. Stories say he would spend weeks on a safari sleeping under the stars, and then show up in New York at Studio 54, barefoot. He was banned from more places than most people are invited into. Iconically described by his friends to “live in a danger zone.”

His home in the Hamptons turned into a creative retreat. The house, filled with artwork, journals, and years of collected objects, was where he spent his final years. His presence is still felt around the East End, his work shows up in local spaces, and stories about him are never in short supply.

His influence is still felt, especially in photography and collage. He mixed media in a way that felt personal, messy, and totally his own, long before that was common. He didn’t follow rules, and neither did his art.

Where to See His Work in NYC:

You can visit the Peter Beard Studio in Chelsea by appointment.

What started as a quiet escape from the city turned into something bigger. This tiny edge of Long Island ended up shaping American art. The artists didn’t come out here for the scene, they came for the space, the quiet, and a little distance from everything else. And somehow, without trying to, they made the Hamptons part of the story of how modern art in America came to be.

I’m in for the Kramer-Pollock visit!